By MDC’s Rural Prosperity and Investment Team

Tense shoulders, shortness of breath, a knot in the stomach—these are physical signs of nervousness when facing new, challenging, or stressful situations. This discomfort is normal: it’s our body’s way of keeping us safe when we feel threatened, even when the threat is not real.

Individual nervousness can permeate organizations and institutions when leaders let their fears drive institutional decisions. Dr. Susan Gooden, MDC board member and Dean of the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs at Virginia Commonwealth University, asserts that racial equity is a “nervous area of government,” one that’s often described as sensitive or challenging. “Issues of equity and justice are fundamental concerns of government,” yet a documented history of “discrimination, bias, and exclusion” makes it uncomfortable for the public sector to engage with it. [i]

The public sector’s nervousness around racial equity—as well as economic and geographic equity—feels particularly pronounced in the South. Our region’s was built on the backs of enslaved labor on land forcibly seized from indigenous communities. Our agricultural sector continues to thrive due to a sizable migrant workforce receiving nominal pay and few government protections. Rural communities in Appalachia, the Deep South, and South Texas have been decimated by extractive industries often subsidized by government. We see the consequences of discriminatory public policies play out today in race-, place-, and class-based disparities in wealth, health, education, and more. Implementing policy that confronts these hard truths requires difficult conversations, and navigating such conversations in the public eye can prompt feelings of shame, uncertainty, and fear among public sector leaders.

As Gooden points out, feeling nervous about confronting inequity is not problematic itself; the key is whether and how the public sector responds. When public sector leaders let discomfort get in the way of addressing inequity, not only is inequity perpetuated but trust is broken between public sector leaders and their constituents. As an example, some community leaders involved in Local Partnerships for Public Funding were met with resistance when they called on public officials to invest in community-identified needs. Instead of listening to residents’ concerns, public officials expressed frustration with community-based efforts to draw attention to the issues. Such “disengagement” from government leaders erodes public trust as community members continue to be left out of decision-making. As community frustration increases and residents pressure government to engage differently, the nervousness that held leaders back initially can become even more acute. All the while, equity issues remain unaddressed, trust diminishes, and the cycle continues.

Public sector leaders must embrace discomfort and tackle equity issues directly. They must do the hard work – and make meaningful investments of time and resources – to build the community’s trust and confidence that the government is acting in the interest of equity. It’s “the only way to shorten the distance between equity in principle and equity in action. Equity in principle makes us feel good. Equity in action confirms that our governments are actually doing good.” [ii]

Public sector professionals need not look far for help when combatting inequities. The best experts are community members most affected by the issue who bring lived “expertise” from their day-to-day interactions with inequitable systems. Intentionally engaging community members with lived expertise builds trust between public sector leaders and constituents, informs government solutions, and demonstrates to communities that they are central to decision-making.

So, what does it look like for the public sector to “step forward by stepping back” long enough to listen to and act on the needs of their constituents?

Authentically engage communities most affected by the issues being addressed.

Historically, the communities most affected by an issue have been left out or excluded from public policy and decision-making. In recent years, we’ve seen the public sector attempt more and better community engagement, though many efforts still fall short. For example, public meetings are held at inaccessible municipal offices during hours when most people are working, or public surveys are distributed online with minimal in-person outreach to communities without internet access.

Some community engagement efforts have been successful though. In North Carolina, state leaders made it clear that local decision-makers can and should lean on their constituents, such as healthcare providers, community organizations, and especially those with lived experience, to decide how to allocate $1.5 billion in opioid settlement funding. Counties that conduct community engagement processes have greater flexibility in how funds can be used, including for housing, transportation, and food. The settlement offers funding over 18 years, which means communities can be creative and think on a larger scale.

Many cities and counties are going above and beyond the minimum public engagement requirements. MDC Rural Prosperity and Investment has worked with community coalitions, like the McDowell Partnership for Substance Use Awareness (PSA) in McDowell County, N.C., to develop recommendations for how to spend settlement funds to address substance use in their community. PSA partnered with McDowell County to facilitate a community-led, participatory process to prioritize the needs of front-line organizations in the community. County commissioners—who had ultimate decision-making authority for how funds would be used—unanimously approved PSA’s recommendations, ensuring that funding reached critical front-line services, including those for harm reduction. Examples like this show that it’s possible for government to prioritize the voices of communities most affected by an issue and ensure solutions closely align with community needs.

Prioritize communities that have been systematically marginalized by past and present policies.

Communities of color, low-income communities, and rural communities have experienced systemic disinvestment from government at various points in our country’s history and continuing today. One recent example: The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) is a grant program that aims to support communities in reducing disaster risks and building climate resilience. However, the distribution of these grants has been inequitable, with only a small percentage of funding awarded to low-capacity rural communities. This is a significant issue as rural areas are often more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and have limited resources to address them. The implications are even more significant in rural communities of color, like the town of Princeville, North Carolina.

Government agencies like FEMA have the opportunity and a public duty to prioritize equity and engage with those most impacted by the issues they seek to address. The North Carolina Real Estate Commission provides an example of what this looks like in action. As of July 2024, prospective home buyers in North Carolina will receive important information about flood history and risk when buying a home. Flood risk disclosure laws educate the public about the hazards associated with climate change, assist people in making better decisions about where to live, and help to foster resilience, especially in communities that are more vulnerable to disasters. However, many states have weak disclosure laws or lack protections altogether. Prior to July 2024, property sellers in North Carolina were only required to disclose whether real estate is in a floodplain; they did not have to disclose whether a property is located in a designated flood hazard zone or has ever experienced damage due to flooding. Purchasing a home at risk of flooding could cost the buyer tens of thousands of dollars in future damage, a cost that lower-income purchasers cannot afford.

The rules changed, however, when the N.C. Real Estate Commission accepted a petition to update the state’s flood disclosure requirements. The petition was led by the Southern Environmental Law Center on behalf of MDC, Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), North Carolina Justice Center, North Carolina Disaster Recovery and Resiliency School, Robeson County Church and Community Center, and NC Field. The Real Estate Commission could have chosen to continue business as usual and continue withholding important flood-risk information from the communities that stand to benefit the most. Instead, they chose to prioritize and protect vulnerable communities that have limited resources to prevent and recover from flooding. “[MDC] joined [the SELC] petition as the convener for the North Carolina Inclusive Disaster Recovery Network,” stated Andrew Loeb Shoenig, Program Director for MDC Rural Prosperity and Investment. “The Commission’s decision is an important step towards our vision of a more just and transparent disaster recovery system.” North Carolina joins a growing number of Southern states that have enacted or improved flood risk disclosure laws.

Uphold public accountability and transparency in decision-making.

“We often hear that ‘people don’t trust the government.’ But a more accurate take would be that ‘the government hasn’t been trustworthy.’” This perspective, shared by a participant at State of the South™: Durham, is particularly resonant for communities of color in the South that have lived through generations of discrimination and false promises from political and governmental institutions. Government must follow through on their commitments to communities to build trust that they are acting in the interest of equity.

In Fayetteville, N.C., community partners that MDC supports through Local Partnerships for Public Funding worked tirelessly to engage and understand the public investment needs of hard-to-reach, economically distressed populations. Their primary goal was to communicate community priorities to elected officials so that officials could make informed funding decisions. Officials originally planned to direct federal recovery funds toward law enforcement and other internal City priorities. Following a community-created documentary and numerous presentations by community organizations, however, elected leaders shifted millions in recovery funds towards emergency and public housing investments. At a public meeting, the Mayor of Fayetteville thanked the organization by name for keeping officials “accountable and transparent,” and the organization gave the officials an award for using recovery funds to address the needs of the community’s most vulnerable.

This work is inherently challenging, particularly in the current political and social climate where issues of equity are being questioned at all levels—from federal challenges to affirmative action and state attacks on women’s rights, to local criticism of institutional diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts. As current events unfold, we’ve watched firsthand as public sector institutions have let nervousness hinder forward progress, or worse, undo progress that has already been made.

In times like this, we need courageous public sector leaders who are not afraid to embrace equity and stand firm when challenged. This will require tough decisions. It may mean shifting funding to address a community-identified issue rather than an internal priority, withdrawing from a longstanding partnership when values aren’t aligned, or challenging colleagues to think or act differently. It’s not always easy or comfortable, but we know that in the long run, these decisions to do good and not just feel good will get us closer to the equitable South we all believe in.

MDC’s Rural Prosperity and Investment team amplifies the voice, capacity, and power of rural communities in the South by strengthening and networking their efforts toward equitable systems and policy change. Lessons in this story are drawn from our work with grassroots, government, and philanthropic leaders, including those involved in Local Partnerships for Public Funding, the North Carolina Inclusive Disaster Recovery Network, and Rural Forward.

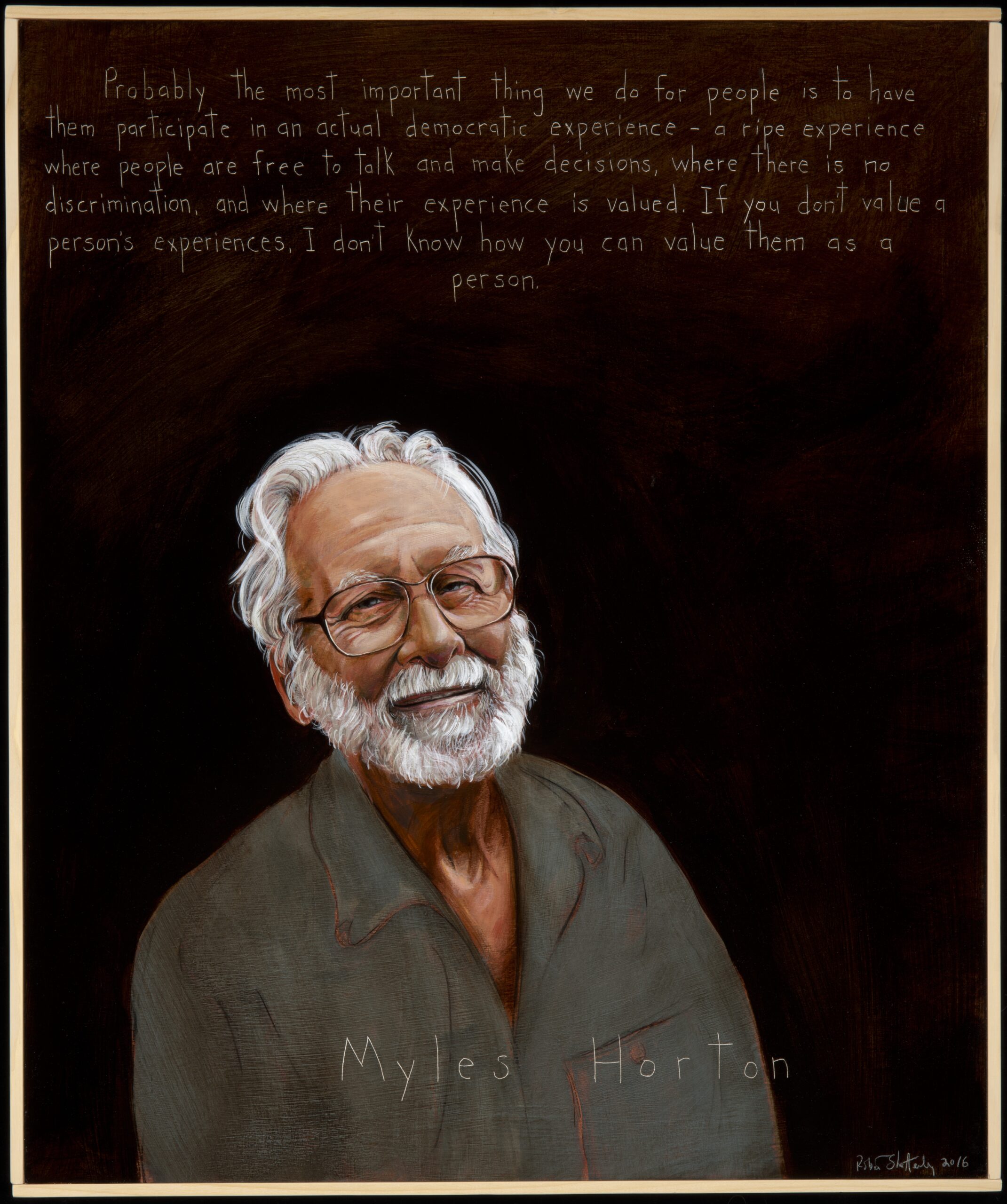

Banner image: Myles Horton portrait by Robert Shetterly, courtesy of Americans Who Tell the Truth, www.americanswhotellthetruth.org