By Peter Hille

It’s time to embrace a new approach to economic development grounded in the realities of the 21st century, not the economies of the past. We must look beyond resource extraction and beyond the industrial revolution to create more diverse, resilient, sustainable, and equitable economies. Appalachia provides a stark example of how the old economy didn’t work. The persistent poverty of this region is a harsh illustration of that failure, and we see many of the same dynamics in rural places across America and worldwide.

The expulsion and erasure of Native Americans and the immeasurable crime of slavery set the economic and moral stage for the extractive industries that have characterized the economic history of Appalachia—from salt to timber to coal to oil and gas. We see the result of what economists call the resource curse: places rich in resources become impoverished.

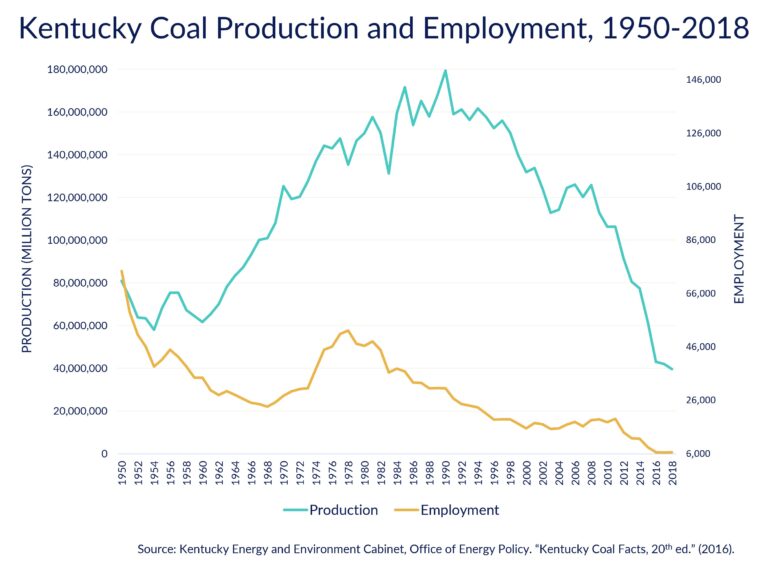

Kentucky began losing coal jobs in the 1950’s and continued to lose jobs for the next 70 years, even as coal production increased. Despite its promise, the old economy didn’t work. Now Appalachia, much like other Southern economies built on extraction, must build a new economy—one that is more diverse, resilient, sustainable and equitable. For more about the economic history of coal in Appalachia and the need for a different future, see Peter Hille’s 2019 Congressional testimony.

For more than 100 years, coal was king in Appalachia. Coal camps were built to house workers. Some had modern conveniences with everything a family needed at the company store. Others offered only a meager existence, and the miners were typically paid in “scrip” that could only be spent at those company stores. As the miners organized for better pay and working conditions, the companies fought the unions with private guards to put down strikes, often violently. Coal brought jobs, but at a great cost to the people and places where it was mined.

Kentucky began losing coal jobs in the 1950’s with the mechanization of the mines. Job loss continued for the next 70 years, even as coal production increased. The jobs became more technical, and paid better, but with each boom-and-bust cycle more workers left, and each time coal rallied, fewer jobs came back. The result is a hollowed-out demographic where generations of workers left to find jobs elsewhere, and many communities lost half of their population.

Today we face the daunting task of building a new economy amid the ruins of an old economy that extracted the coal, extracted the wealth, and ultimately extracted the workforce. Building a new economy in Appalachia will take more than just bringing in a new industry to replace the old one. We have to rebuild entire local economies with all the elements of community that are needed to support it—schools, healthcare, childcare, housing, and infrastructure.

Local leaders have stepped up to the challenge of recreating their communities as places where people can live and will choose to live. They understand that all the services and amenities that make a place livable are themselves economic drivers—grocery stores, coffee shops, bookstores, restaurants, recreation opportunities, health clinics, and childcare centers.

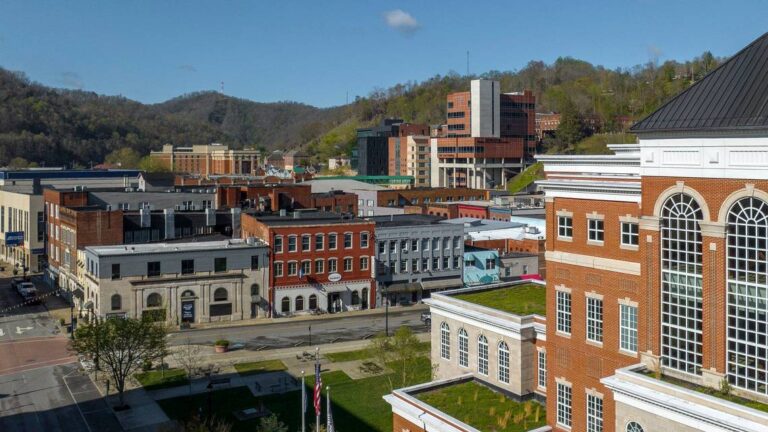

Remarkably, we now stand at an exciting moment in this long trajectory. An April 2023 article in the Lexington Herald Leader headlined “Thriving Business Climate” described the growth of retail businesses in several Eastern Kentucky downtowns. The article cited places where old downtown store fronts are filling up, where it’s become hard to find a place to open another business, and one town where occupancy has gone from 80% vacant to 100% full. This feels like a tipping point in the long work of community economic development in the region.

How did we get here? These communities are growing again because of decades of investment in local leadership and community development. Seeds of hope were sown through countless small projects carried out by local leaders—a park cleanup, a new farmers market, an after-school program for kids, or a walking trail. These seeds were watered by resources like community mini-grants programs, support from community foundations, and local fundraising that unearthed untapped assets. The saplings that took root now bear fruit as young people see the changes and begin to imagine a future for themselves that doesn’t require them to leave. Those who left are considering coming home, and visitors are wondering if they might set down roots here, too.

This tipping point in our journey of community revitalization coincides with a sea change in the world of work. In the past, jobs were tied almost exclusively to physical locations. Much of the old-school language of economic development spoke of this in well-worn phrases like “bringing in jobs” or “landing a factory.” The world of online work has been shifting that paradigm for many years, but today, in the post-pandemic economy, we have learned the true extent to which many jobs need not be tied to a physical location.

For Appalachia, this bodes well for an approach to community economic development grounded in the idea of communities where people want to live and can afford to live. Our re-awakening downtowns, combined with the natural beauty of this area, provide an attractive quality of life. The opportunity for people to live here without sacrificing the potential of a world-class job is a bright light at the end of a long tunnel.

Coal communities literally fueled the growth of our nation’s economy, but despite their sacrifices, they did not participate in the prosperity they helped create. They are owed a debt—a debt that can be paid by investing in growing this new economy. The federal government has recognized that debt with a breathtaking range of new funding programs for energy communities, but it is critical that we ensure these resources are not squandered in outmoded approaches like building industrial parks to recruit industries—industries that are not likely to locate in the small, economically distressed counties of this region.

Instead, government policymakers and private philanthropy should hearken to voices close to the ground, align their investments with the good work that is already underway in many places, and help communities that are just getting started to begin their own revitalization. Many of our towns have attractive old buildings that have sat vacant too long—invest the money needed to bring them forward into this moment of rebirth. Our schools are struggling for funding—put solar panels on their roofs to reduce their energy burden. We have a long-standing housing crisis, made worse by climate-driven storms—put new federal dollars into meeting that need so as our population rebounds, people have decent homes to live in.

Our communities are coming back to life and we can see the positive results. People are returning, and many of them are bringing their jobs with them. The new economy we are building here in Eastern Kentucky can be an example for rural places everywhere. When local leaders and local entrepreneurs take control of their own economic future, and create communities where people want to live, the people will come, and the jobs will follow.

Best practices for strengthening economic resilience in Appalachia – and rural communities throughout the South

- Invest in education, technology, infrastructure, and broadband.

- Engage the community over the long term.

- Create communities where people want to live.

- Grow youth engagement and next-generation leadership.

- Identify and grow the assets in the community and region.

- Build networks and foster collaboration.

- Move multiple sectors forward for economic development and grow value chains.

- Cultivate entrepreneurs and develop resources for business start-ups.

Strengthening Economic Resilience in Appalachia: A Guidebook for Practitioners includes case studies and best practices for enhancing economic prospects of coal-impacted communities in Appalachia, but the lessons apply to other Southern, rural communities historically dominated by one industry.

Peter Hille is CEO of the Mountain Association, a nonprofit CDFI that invests in people and places in Eastern Kentucky to advance a just transition to a new economy that is more diverse, sustainable, equitable and resilient. Over the past 13 years Peter has helped expand Mountain Association’s work in many ways, including growing Appalachia’s clean energy sector, creating accessible lending products for underserved entrepreneurs, and participating in national policy efforts to advance economic transition for coal communities. Previously, Peter was Director of Berea College’s Brushy Fork Institute, working in leadership and community development throughout Central Appalachia for 22 years.

Banner image: Dove of Peace Mural by artist C. Finley. Credit: City of Hazard, Kentucky