Income and Wealth for All: The Foundation for a Just Economy

Hope Wollensack and Amit Khanduri

Every November, nearly two-thirds of eligible voters participate in consequential local, state, and federal elections that determine the future of our democracy. Each vote, a reinforcement of civil and political rights, is a foundational and widely understood component of the democracy we hold dear.

An often overlooked but equally crucial aspect of a strong democracy is economic rights: a base level of resources to foster meaningful opportunity and full participation in society. Without this, choice, freedom, and self-determination are hollow concepts.

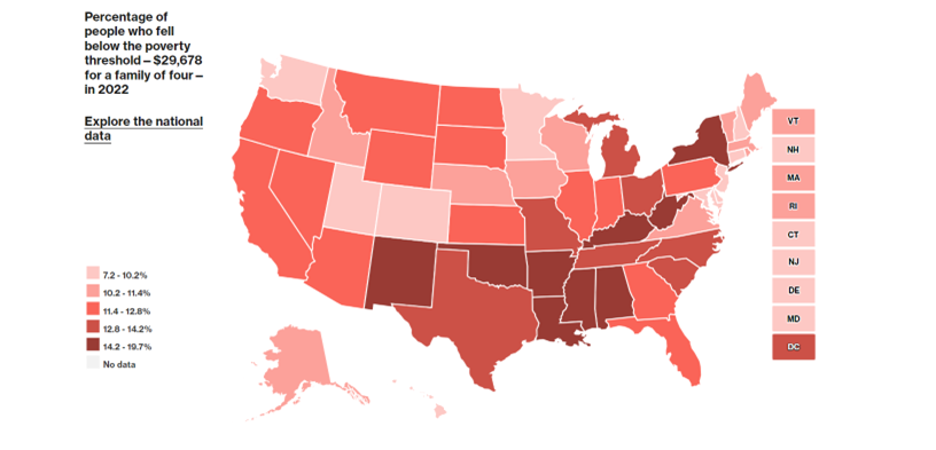

Almost 40 million Americans, half of whom reside in the South, live in poverty. The bottom half of Americans, by wealth, share 2.5% of the nation’s wealth. This stands in stark contrast to the foundational promise of American democracy.

Source: Center for American Progress. “Poverty in the United States: Explore the Map” (2024). Accessed October 2, 2024. https://www.americanprogress.org/data-view/poverty-data/poverty-data-map-tool/

The racial wealth divide is wide and persistent across the South.

The South is the largest and fastest growing region in the U.S., and is home to the majority of the nation’s Black population. With the largest congressional delegation of any region—and an outsized influence on presidential elections—the region holds substantial political power.

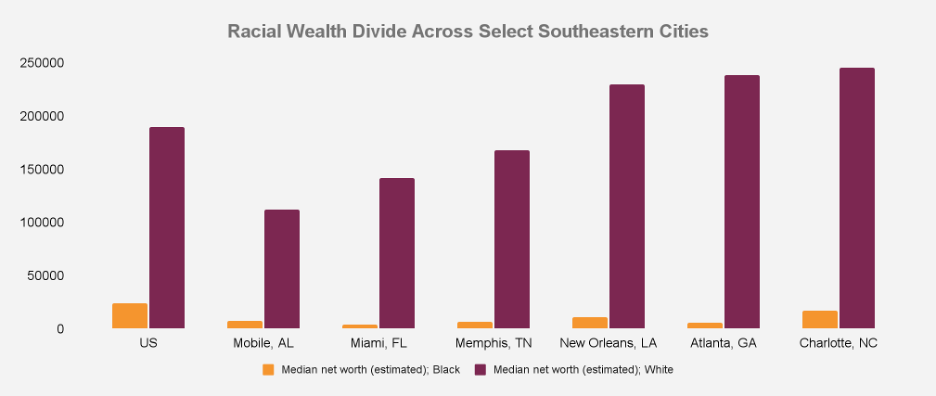

Yet the South has one of the most significant racial wealth disparities in the nation. When it comes to anti-Black economic exploitation, every region of the United States is culpable, but the South has some of the widest racial wealth divides.

The White-Black racial wealth divide has remained the same for 70 years and will likely worsen, given current trends. Across the U.S., the racial wealth divide is 6:1. The divide is even starker in many Southeastern cities. The racial wealth divides in Atlanta, Ga., Houston, Texas, and Greensboro, N.C., are 46:1, 47:1, and 87:1. This means the average White household has 46 times, 47 times, and 87 times more wealth than the average Black household, respectively. The wealth divide in these cities is as high or higher than the national racial wealth divide in 1863, just after Emancipation.

Source: Urban Institute. “Financial Health and Wealth Dashboard” (2022). Accessed October 2, 2024. https://apps.urban.org/features/financial-health-wealth-dashboard/

According to Prosperity Now’s landmark report, “The Road to Zero,” without intervention, median household wealth for Black Americans will fall to net zero by 2050. If Black wealth continues to grow at today’s rate, it will take Black families 228 years to amass the amount of wealth White families have today.

Every year, there seems to be a new statistic that confirms what impacted communities already know to be true: the economy isn’t working for them. Take Atlanta, for example. If you live in Section 8 housing in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward neighborhood, you don’t need to know that the racial wealth divide is 46:1 because you see the multi-million dollar homes spring up alongside your modest residence. If you’re a teenager in Atlanta’s West End neighborhood, you don’t need to be told that Atlanta is perennially among the worst cities for income inequality because selling water on the side of the road is the most lucrative job option available to you right now. And if you’re born in Bankhead, you don’t need to be reminded that your life expectancy might be 20 years higher if you were born in the neighborhood six miles away because you confront the realities of disinvestment every day.

Policy choices direct wealth accumulation; wealth is not naturally occurring

Public policy has undermined economic opportunities for, and extracted wealth from, Black communities and directed wealth into White communities. The wealth divide has grown, even when explicitly discriminatory policies are removed, and the law has become “colorblind.” Indeed, the conditions that have created today’s racial disparities in wealth are “in the groundwater.”

Consider this: Ostensibly a “color blind” program, the GI Bill is widely credited with building the White middle-class post-WWII through education and housing subsidies. When it was administered, it often excluded or provided significantly reduced benefits to Black veterans. This program has had significant intergenerational effects: The descendants of White veterans have 32 times more wealth than the descendants of Black veterans.

Since the 1980s, capital gains are taxed at a far lower rate than income. Stock equity has appreciated five times as much as housing wealth since the 1950s – a boon to White households who hold three times as much stock equity as Black households.

Source: Perry, Andre M., Hannah Stephens, and Manann Donoghoe. “Black wealth is increasing, but so is the racial wealth gap,” Brookings (January 9, 2024). Accessed October 2, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/black-wealth-is-increasing-but-so-is-the-racial-wealth-gap/

Income and wealth are key drivers of the racial wealth divide

Many traditional approaches to close the racial wealth divide only address the symptoms of underlying issues, not root causes. Symptoms of the wealth divide include disparities in homeownership, entrepreneurship, higher education, and retirement savings. Strategies that seek to address these symptoms focus on changing individual behavior, through financial literacy programs for example, or by increasing wealth indirectly through job training or small business ownership. However, these do not address the root cause nor the scale of the wealth gap.

The root causes of the wealth divide are income and wealth itself. The large earnings gap between White workers and Black workers contributes significantly to the wealth divide. Typically, wealth is accrued from interest on previous wealth and new savings from income. Without adequate wealth and income, individuals cannot start businesses, buy a home, or attend university. In short, inadequate wealth and income are the key barriers to asset accumulation.

Home equity is the largest source of wealth for most households, particularly Black households. The National Association of Realtors estimates that only 17% of White renters and 9% of Black renters nationwide can afford to buy a median-priced home in their area. Common reasons lenders cite for home loan denials to Black applicants include insufficient funds for down payments and high debt-to-income ratios, both a direct product of insufficient wealth and income. This same story is true for entrepreneurs seeking a start-up loan from the Small Business Administration or high school seniors looking to get a postsecondary degree. Their and their families’ income and wealth will determine what is possible and drive future wealth outcomes.

Income and wealth are cornerstones of a just economy

Closing the racial wealth divide requires addressing the root causes of inequality. Two hallmarks of a just economy are adequate income and wealth: cash for today and capital for tomorrow. At the Georgia Resilience and Opportunity (GRO) Fund, we bring to life these two core tenets for a just economy through our guaranteed income (GI) and Baby Bonds (BB) pilot programs. GI provides regular, unrestricted cash to households, which creates an income floor to support basic needs. BB provides “investable sums” to build wealth by helping to pay for college, start a business, or purchase a home.

These programs disrupt dominant narratives about poverty, build the public’s understanding of an inclusive economy, provide dignity and choice, and are foundational policies for a more just economy. Together, they are powerful solutions for an economy where we all can thrive.

For one participant in GRO’s GI program, the unrestricted cash transfers helped her spend more time with her children:

“I used to always work, work, work, work, work. I never really got to see my kids because of my work schedule. But now I’m able to spend time with my children and do things like pick them up from school, take them to practice, and cook them dinner. This extra income has taken a lot of stress off my shoulders and let me spend more quality time with my kids.”

The ability to spend more time with family contributes to this participant’s happiness and overall well-being, which is a direct result of having a consistent source of income that allows her to have choice in employment and delegation of her time.

This is what a just economy could look like. Instead of directing how people in poverty live their lives, as current social safety net programs do, a just economy centers the humanity of all people. It enables them to live dignified, self-directed lives. A just economy – one that invests in all people by providing an income floor through GI and a real opportunity to build wealth through Baby Bonds – addresses the root causes of the racial wealth divide. If implemented nationally, a guaranteed income would end poverty; a Baby Bond would reduce the racial wealth divide for young people by up to 50%. Building a just economy will fulfill a central promise of our democracy: that all of us have the undeniable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

“As the South goes, so goes the nation.”

The South remains central to the struggle to realize this nation’s founding ideals. Today, regressive policies – from anti-labor policies to voter suppression legislation – are often piloted in the South before being exported to other parts of the country. Yet the South continues to be home to innovative and bold approaches to building an economy that works for everyone.

As history has shown, the South is central to achieving civil and economic rights – and this isn’t just a relic of the past. Consider the following examples. The nation’s first guaranteed income program was created in Jackson, Mississippi, by Aisha Nyandoro through her Magnolia Mother’s Trust initiative, which sparked more than 100 pilots nationally and arguably laid the groundwork for the Child Tax Credit. The work of Stacey Abrams’s Fair Fight and New Georgia Project helped deliver a Democratic Senate majority, which ensured the passage of the American Rescue Plan, the largest stimulus package in history. The Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Sites, led by Brian Stevenson, has molded our collective discourse on the legacy and enduring impacts of slavery. All Black-led and ground-up efforts, these contributions have resonated nationally, inspiring communities across the country and shaping national elections and policy.

One hundred and eighty years after the end of slavery and 103 years after the Tulsa massacre that decimated a burgeoning Black Wall Street, a reinvigorated Southern Black belt could drive the development of a just economy. To achieve this, we must be willing to address the root causes of poverty and wealth inequality and establish universal access to wealth and income. Only then can a just economy be built.

Hope Wollensack is the founder and Executive Director of the Georgia Resilience & Opportunity (GRO) Fund. GRO brings to life bold, evidence-based and community driven solutions to eliminate poverty and narrow the racial wealth gap. GRO’s work includes the In Her Hands’ guaranteed income program, a $30M initiative, and the first accelerated Baby Bonds pilot program. Hope began her career as an organizer, teacher, and assistant principal, and before her current role was a senior strategist at the Economic Security Project. Hope earned her Master of Public Affairs from Princeton’s School of International and Public Affairs and a Bachelor of Arts from Tufts University, where she helped found the Africana Studies program.

Amit Khanduri serves as Director of Programs for the Georgia Resilience & Opportunity Fund, where he leads GRO’s Baby Bonds pilot program and efforts to address the racial wealth divide. He holds a decade of experience driving bold solutions to narrow the racial wealth divide through strategies ranging from cash transfer programs to community development. Prior to GRO, Amit was a Senior Program Officer at LISC Atlanta. Amit helped to establish LISC’s new Atlanta office, and directed and advised the deployment of $50M in community development investments to improve financial stability, wealth, and well-being. Amit holds a master’s degree in public policy from Duke University and a Bachelor’s degree in Business Administration from Georgia Tech.